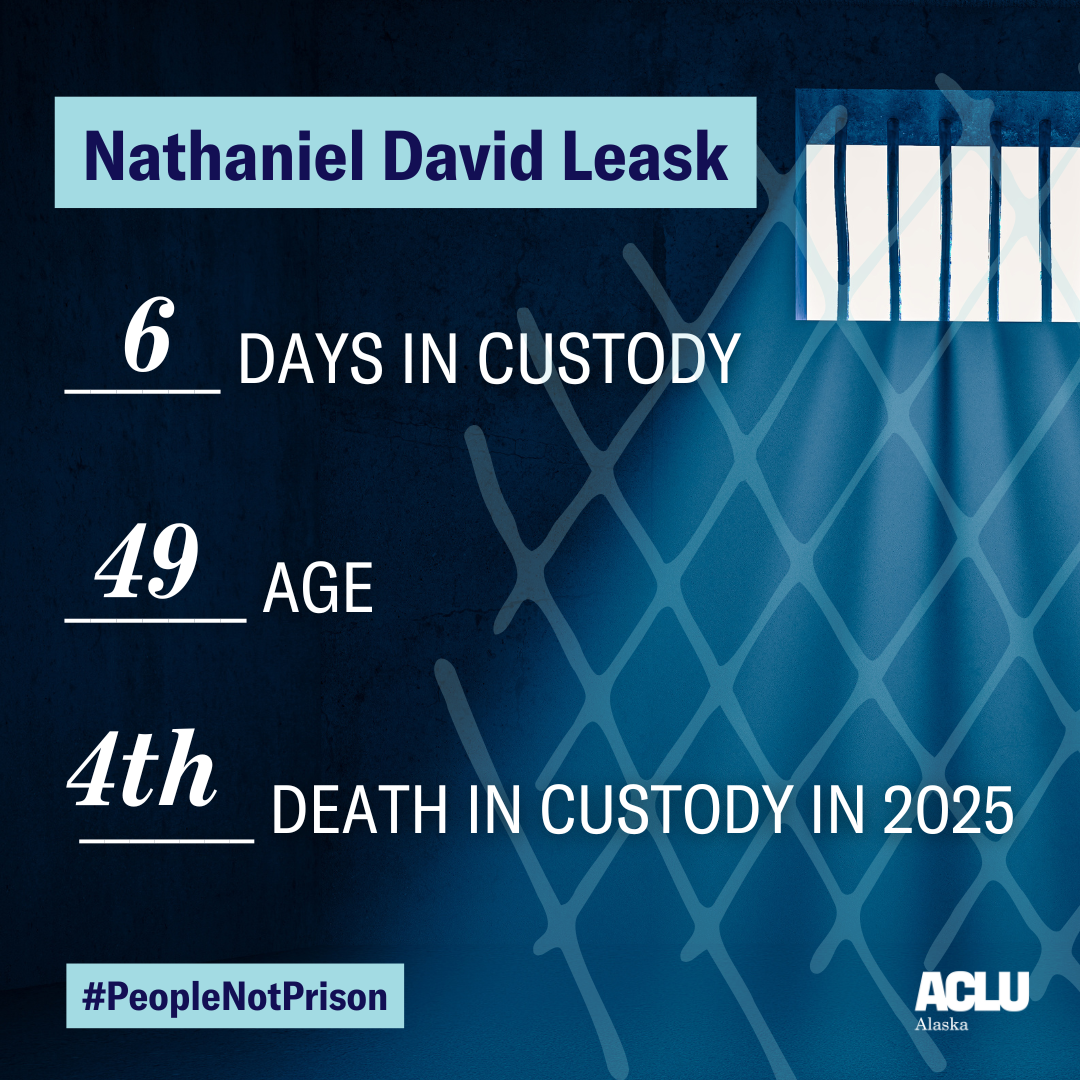

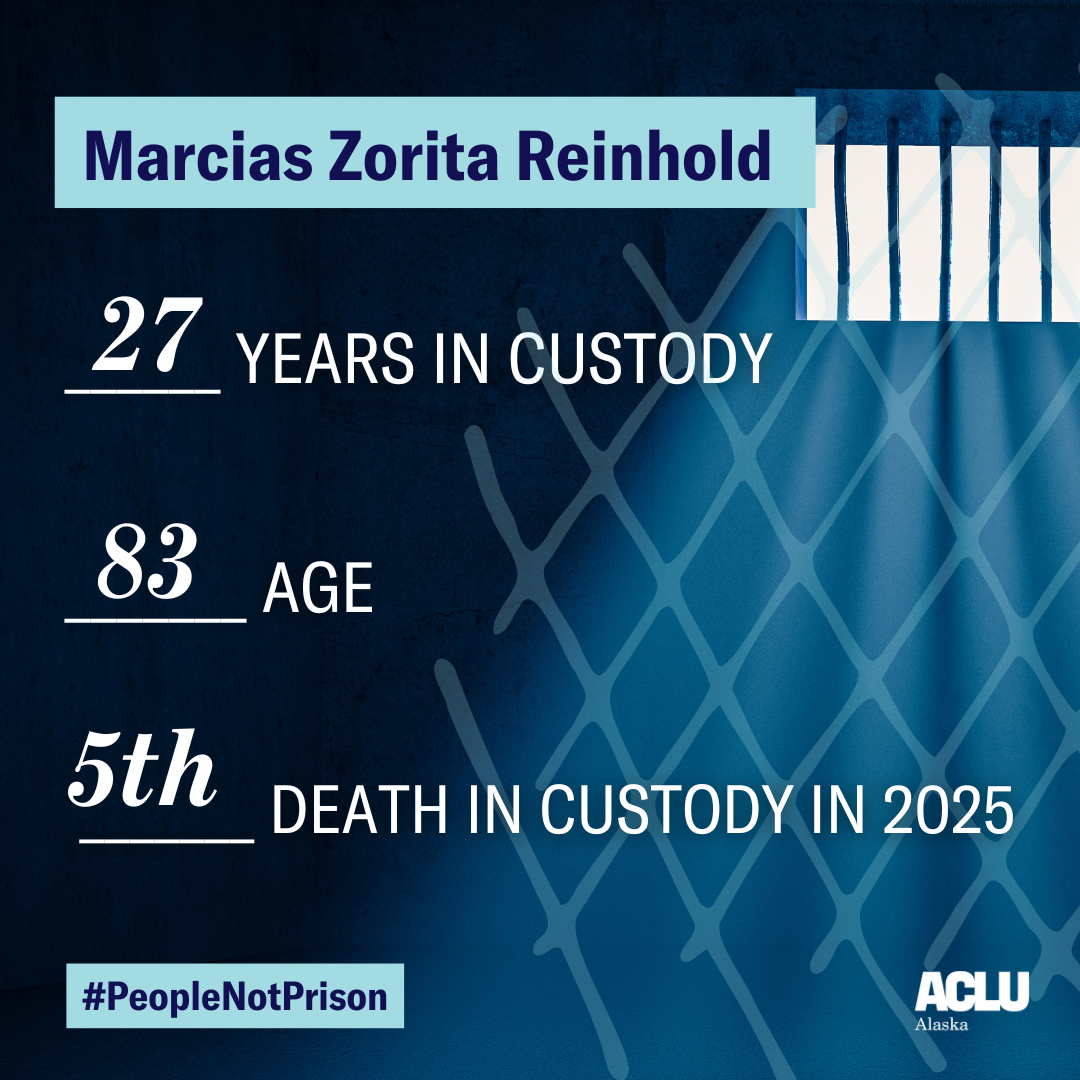

Since last week’s House Judiciary Committee two-hour hearing about deaths in custody, and the deaths the Department of Corrections (DOC) neglected to count, two more people have died. By DOC’s tally that makes four deaths this year, but by our count it’s five. The most recent deaths follow tragic trends discussed in the March 31 hearing.

At least 51 people have died in an Alaska state jail or prison, or as a result of treatment in custody, since 2022. DOC has been hesitant to provide real details about why so many Alaskans are losing their lives in their care, but the hearing in House Judiciary last week finally began to provide insight.

Here are our big takeaways:

- DOC doesn’t count deaths that occur once a person’s custody status changes. For example: They did not count the deaths of William Farmer, Angelena McCord, Lewis Jordan, or Jimmie Singree because, although their deaths were a result of the conditions they experienced in jail or prison, their legal/custody status changed. This concerned the committee, as it raises the question of how many other deaths were not counted.

- Specifically, Farmer was assaulted by his cellmate and was unconscious when he was taken to the hospital from prison, but his bail conditions changed a week later. Charges against McCord were never posted online but appear to have been dismissed, Jordan was paroled while in a coma, and Singree left a Kenai prison brain dead and was also discharged. Dr. Timothy Ballard, DOC’s Chief Medical Officer, told the committee that he loses medical authority when custody status changes.

- But because Alaska State Troopers investigate deaths in custody and the State Medical Examiner determine cause of death, and all agencies can speak to each other, it is entirely possible to assume they could report to DOC when someone has died, and DOC could list it as a death.

- Dr. Ballard’s explanation also doesn’t explain why DOC didn’t report Ross Greenley’s death. Greenley was arrested by Anchorage police during the summer of 2024. He asked to go to a hospital, but according to a report by the Office of Special Prosecution, police officers told him he’d get medical care in jail. He died chained to a wall in booking at ACC.

- Specifically, Farmer was assaulted by his cellmate and was unconscious when he was taken to the hospital from prison, but his bail conditions changed a week later. Charges against McCord were never posted online but appear to have been dismissed, Jordan was paroled while in a coma, and Singree left a Kenai prison brain dead and was also discharged. Dr. Timothy Ballard, DOC’s Chief Medical Officer, told the committee that he loses medical authority when custody status changes.

- The mental health crisis is growing, and DOC shouldn’t be the de facto care provider for mental health. Farmer’s death highlights this most greatly. Despite being diagnosed with schizophrenia, DOC placed him in a cell with two other people, including another man with schizophrenia who, only days earlier, had been found incompetent to stand trial. Law enforcement officers say he beat Farmer, knocking him unconscious in less than 60 seconds. As DOC said in the March 31 hearing, and in many other settings, they believe this vulnerable population would be better served in community therapeutic settings. Unfortunately, few of those opportunities exist – especially for those facing criminal charges.

- All state agencies should be better coordinated with families.

- As Joshua Zimmerman’s sister, Alaina, stated in her testimony to the House Judiciary Committee, DOC first told the family “no foul play is suspected” (this statement remains on DOC’s website), but after months of no answers they finally tracked down a Trooper and the Medical Examiner who informed their family that Joshua Zimmerman had been suffocated with a soft object and murdered. A grieving family should never have to track down law enforcement, information should flow the other way.

- William Farmer was hospitalized before his death and his sister, Robin, found out “through the grapevine.” If her brother’s assault had occurred in a place in which he wasn’t detained, it is much more likely law enforcement officers would have reached out. They didn’t, though. Then the Farmer family was punished as they said their final goodbyes. Robin Farmer raised concerns about the bed sores her brother had developed where he was shackled to the bed. So, DOC banned her. And for her to restore her right to say goodbye, she had to visit a local jail, where she said officers berated her. She sent multiple unanswered emails to department officials. When she could visit again, staff gave a series of inconsistent “rules” about how long the family could visit.

- As Joshua Zimmerman’s sister, Alaina, stated in her testimony to the House Judiciary Committee, DOC first told the family “no foul play is suspected” (this statement remains on DOC’s website), but after months of no answers they finally tracked down a Trooper and the Medical Examiner who informed their family that Joshua Zimmerman had been suffocated with a soft object and murdered. A grieving family should never have to track down law enforcement, information should flow the other way.

- Lack of DOC oversight. DOC says when someone dies, they conduct an administrative review. Superintendents from facilities other than the one at which the deceased was housed, along with staff from DOC’s central office, review security information and medical records. DOC told the committee that staff from other facilities do this review to uphold a level of objectivity, but the review is still internal. They said they believe Troopers provide another level of transparency, as a separate agency. According to DOC, the review team looks at everything - what went right and what went wrong - so they can improve. But DOC does not make details of those reviews public, and public records are hard to obtain without legal action. Without external oversight, it’s impossible to know what problems exist, how they are being corrected, and if the department has the resources to make the necessary changes.

Although the hearing didn’t discuss it, the latest deaths highlight other troubling trends, including people dying in custody after being taken back into custody for nonviolent technical violations while on community supervision. And, for Reinhold, it raises questions about how Alaska uses parole as people age into their 80s or 90s, when they are extremely unlikely to commit new crimes, much less violent ones. At the same time, their medical care becomes more complex and expensive to provide within the prison system. It is unclear whether or not she was eligible for or had been denied discretionary parole, and was not eligible for geriatric parole because of her convictions.

These discussions are nuanced, but last week’s hearing dug into the details and opened the door for policy solutions. We believe the solutions should improve transparency and accountability for the department, increase efficiency between agencies, and ultimately help deliver justice for all those interacting with the criminal legal system.